Where is the craftsmanship in a computer-generated object? And when does studied imperfection produce appealing results? Designer Thorsten Franck has a particular interest in the connections between material properties and design. His understanding of design has its roots in his training in carpentry. This was followed up by a course in design with Wilkhahn designer Werner Sauer in Hildesheim, which he continued at the Royal College of Art in London. After previously developing the Stand-Up mover with Wilkhahn in 2012, he got to work exploiting the full possibilities of 3D printing and environmentally-friendly production with the PrintStool One, launched in 2016. We spoke to Thorsten about his fascination with simplicity, the relationship between hyperboloids and African stools and what links basket weaving and 3D printing.

You believe it’s very important that design reflect the materials it uses. How is this the case in the PrintStool?

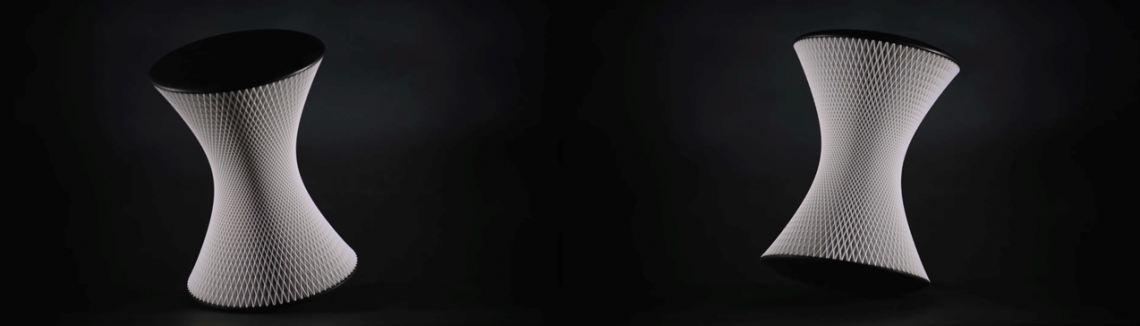

Here, as ever, I was interested in developing a distinct design language for 3D printing rather than producing molds using 3D printing technology. In the case of the PrintStool, I applied FDM (fused deposition modeling), in which material is positioned and hardened from a filament. Designing with the filament was central to my approach, and that’s also why I associate it with basket weaving. The strength of the material is produced in a very similar way, with a kind of CNC (computerized numerical control) basket weaving. That’s the element of craftsmanship that you’ll frequently find in my work.

Basket weaving always involves two elements, a rigid one and a flexible one. Is that also true here?

Thermoplastics perform the function of the stakes. The cross layers are not connected in basket weaving, but they are in 3D printing. The structures, however, are similar to those in basket weaving, for example the PrintStool’s waffle texture: basically, I have a large number of small dimples, i.e. indentations, which help to harden the filament construction and thus stiffen the material. Accessing these structures was a complex job, as neither the software nor the printers are sufficiently sophisticated. Everyone was bowled over by the very first stool we printed because the technology had worked, the material had played along and the level of quality we desired had proven to be achievable. In contrast to other manufacturers working to find an “even finer filament”, we consciously settled on a certain “coarseness”. This produced very attractive traces of the production process and lends the stool a distinctive textile character.

And how did you decide on the shape?

The shape is a hyperboloid. It came about in the course of considering what could be easily generated mathematically and worked without problems. Woven stools in Africa look exactly the same, by the way. Hyperboloids save considerably on materials, at the same time featuring excellent strength.

Just like in architecture. Hyperboloid shells are complex, double curved geometries copied from nature.

Right, it’s the naturalness of this geometry that also suits a stool well. On the one hand, I enlarge the surface with the dimples, at the same time reducing it by “pulling in” the structure at its center. This was done to prevent excessively long printing times. The quantity of material used equates to around a bag of milk, i.e. a liter or a kilogram. And what’s great about it is that I have excellent control over the material: I can print it thicker or harder wherever it’s not rigid enough.

How did you arrive at lignin as your thermoplastic?

At the end of the day, 3D printing is about innovating in every respect. Our innovation here is that we work with an endless spiral, what is known as the Joris spiral, which has no “seam”. Lignin is a fully biodegradable material and a further step toward true innovation. Two principles of my design are “reduce to the max” and “minimum energy structures” – and they apply throughout the value chain.

If you could choose any celebrity to sit on the PrintStool, who would it be?

I’d be happier if this stool actually became an everyday object, actually! After all, the technology offers us the opportunity to turn it into a global product. I can see a mechanic, for example, sitting on the stool in a car repair shop. Like a milking stool in earlier times, the PrintStool supports dynamic sitting, it’s about having a brief rest between activities. I would, however, also be delighted if Jochen Hahne were to sit on this stool in his office, in counterpoint with Wilkhahn’s office chairs, as it were.

I can really understand that, what with PrintStool One’s “unassuming” formal presence. Many thanks, Thorsten Franck, for talking to us.

More about Thorsten Franck

More about PrintStool One